The Good: gender issues

The Good: gender issues

The Bad: gender issues

The Ugly: gender issues (and I foresaw the twist at the end)

Setting: US in the near future

Recommended for: thriller and suspense fans,

people interested in human factors in technology

innovation and adoption

When I heard Bruce McCabe speak at the National Book Bloggers Forum about his debut novel, Skinjob, I was hooked. Not by the title. If I’d seen that title on the library shelves, I wouldn’t have picked it up without gloves. When I first saw it, it reminded me of “hand-job”. It still reminds me of hand-job, even though I’ve read the book and there’s nothing titillating in it. Exciting, yes. Adventurous, yes. It has all the elements Robert McKee writes about in Story: a ticking clock, a vulnerable hero, powerful antagonists, and an interesting (pretty “high”) concept.

The concept: what could happen when robotics advance to the extent that the “world’s oldest profession” can be performed by robots, “Skinjobs”? What if the powerful forces of the pornography/sex trade industry and the neo-conservative Christian right waged an epic battle to sway the hearts and minds of the American people? What if a lie-detecting FBI agent and a San Francisco PD (female) surveillance officer teamed up in a race against time to prevent the annihilation of thousands of innocent people?

Juicy stuff, right? It is. And McCabe does it well. Well enough to have gone from being a self-published author hand-selling to Berkelouw Books in Dee Why to attracting the attention of J K Rowling’s agent and scoring a contract with Random House.

What really interests me about the book, though, is its take on gender issues.

Some background.

At the book bloggers’ forum, I asked Bruce McCabe whether he read books by Australian women. No, he is more of a Michael Crichton, Frederick Forsyth and Stephen King guy. (All of whose books I have devoured.) Also Lee Childs. He did say that author Kathryn Fox had been very helpful to him though (she appears in the acknowledgements) and added, “I must read her books”.

It was with amusement and some consternation, therefore, that I came across a cameo appearance of a “Kathryn Fox” in McCabe’s novel.

The title of the novel, Skinjob, refers to an advanced form of sex doll. These life-like dolls have warm “skin”, a “heartbeat”, and can move in a “come hither” fashion. They can’t speak, but can make moaning and groaning noises. They don’t act other than to flirt or serve. They can also simulate realistic fear to threats and acts of violence (up to the point of actual physical harm). “Kathryn Fox” appears in the book as one of the manufacturer Dreamcom’s most successful dolls.

What is McCabe trying to say here?

One thing McCabe talked about at the forum was how there is no good and bad in human beings; we all have elements of both. The main character, Daniel Masden, isn’t perfect. Nor is the female SFPD operative, Shahida Sanayei (Shari), whom Masden partners up with. Shari, in fact (spoiler alert) solves the enigma that is central to the plot and, therefore, effectively saves the day.

All good. But what if Skinjob became a movie – as it certainly could; it’s very filmic, action-packed and fast-paced, has lots of interesting “locations”, high-tech gadgetry and car chases – would it pass the Bechdel Test? That is, does it have “at least two women who talk to each other about something other than a man”?

It wouldn’t. That’s right. A story in which gender issues are crucial, all bar one of the main character roles are male. Shari is introduced in the context of having lost her male lover in a bomb-blast at a skinjob “brothel” – or pleasure house – run by Dreamcom. Her role in the story is to help Masden track down those responsible for the blast; all the suspects are male. The SFPD major figures and FBI personnel are male; the Dreamcom owners and employees are male; the leaders of the right-wing church suspected of being behind the blast are male. The majority of the “females” who would appear in the movie would be robots. (Imagine doing that screen test.)

Remember Skinjob is set in the future. Even if one asserted that the industries depicted in the story are currently male dominated, there is plenty of scope in a future world for more than one woman to be depicted as having agency and moral complexity. Why not a female pastor? A female pleasure parlour owner? Sure, the men in these roles in Skinjob don’t come off well and are often revealed to be self-serving hypocrites, sex-addicts and narcissists. That shouldn’t be a restriction. As McCabe was at pains to point out, human beings are complex moral creatures; that includes women.

In Skinjob McCabe sets out to address some really interesting questions about gender, sex and power, the most interesting of which, for me, is the ethics of using automatons for sexual relief. But, while writing about it for entertainment, he risks reinscribing the very kind of objectification and invisibility of women which, arguably, the sex industry and fundamentalist churches of all kinds have historically been guilty of.

My conclusion? It’s still a page-turning read.

~

This review forms part of my contribution to the Aussie Author’s Challenge 2014

Review copy courtesy of the publishers at the National Book Bloggers Forum.

ISBN: 9780593074091

Published: 02/06/2014

Imprint: Bantam Press

Extent: 416 pages

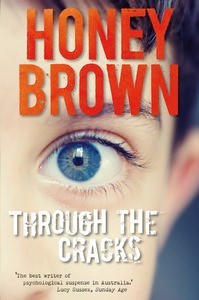

I never read the back covers of their latest. So I knew very little about Honey Brown’s psychological suspense novel, Through the Cracks, before I picked it up. Later, I read through some reviews posted for the Australian Women Writers challenge and saw that several reviewers were dismayed and annoyed that the book’s back cover “blurb” gave away a lot of the story’s suspense. So, fair warning: don’t read the back cover.*

I never read the back covers of their latest. So I knew very little about Honey Brown’s psychological suspense novel, Through the Cracks, before I picked it up. Later, I read through some reviews posted for the Australian Women Writers challenge and saw that several reviewers were dismayed and annoyed that the book’s back cover “blurb” gave away a lot of the story’s suspense. So, fair warning: don’t read the back cover.*