![KandyShepherd_ReinventingRose[3]](https://elizabethlhuede.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/kandyshepherd_reinventingrose3.jpg?w=200&h=300) When I first read Reinventing Rose it was in manuscript form and I knew it by a different title, The Love-Rat Ritual. It’s this early title I love. It wasn’t right for the US market, though: apparently US readers don’t know what a “love rat” is; so it had to go.

When I first read Reinventing Rose it was in manuscript form and I knew it by a different title, The Love-Rat Ritual. It’s this early title I love. It wasn’t right for the US market, though: apparently US readers don’t know what a “love rat” is; so it had to go.

Honestly? I didn’t know what a love rat was, either, before I read the book, but this story set me straight. It features quite a few love rats, old, young, gay, straight, male, female. They are human beings who, in their search to find The One – a man or woman with whom they might just possibly create a happy life – sometimes behave badly. Most of us, the story hints, have been love rats at one time or another. Love is tricky, but worth searching for.

With the characteristic humour which fans of Shepherd’s previous award-winning and best-selling novels have come to love, Reinventing Rose tells the tale of a newly divorced school teacher from Bookerville, California. After having met her internet lover Scott offline for outrageously good sex, Rose buys a ticket and flies to Sydney to hook up once more with her handsome Aussie hunk. It’s the start of the US summer school holidays and she’s giving her adventurous side full rein. On arrival, however, she discovers Scott’s not only married, but also his wife has a baby. He’s a love rat of the first order, and only too happy to get rid of Rose before she even leaves the airport.

Scott’s betrayal isn’t the only unwelcome discovery Rose makes as we follow her adventures “down under”. Her struggles to reinvent herself as a stranger in a strange land, however, are made a whole lot easier – and funnier! – by her outgoing Aussie flatmates, botoxed beauty editor Carla and artist-cum-trust-fund heiress Sasha, as well as their fiercely independent neighbour and friend, international model Kelly. These girls – women – are drawn with flair and deserve to star in books of their own.

The humour that propels this story wouldn’t have been possible without Shepherd’s inside knowledge of Sydney’s magazine scene. At the back of the book, Shepherd writes:

One of the things I most enjoyed during my years in women’s magazines was working with reader makeovers. There was something thrilling about helping transform women (and sometimes men) of all ages with the right hair, makeup and fashion advice. Often the makeover gave such a confidence boost it led to positive change in both relationships and career.

Here Shepherd emphasises the transformative powers of the makeover, and this is certainly an important element of the story. What strikes me more, however, are the makeover’s comic absurdities which Shepherd depicts with compassionate good humour, along with the seemingly never-ending obsession these women have in their attempts to look beautiful, to fit in, to attract the right kind of mate.

The story has a deeper side, too, as Rose struggles to come to terms with what she learns about her dead father, that her parents’ “happy ever after” was at the cost of him hiding his sexuality. Rose grows in self-awareness as she reconciles herself with and finally accepts what initially she perceives to be his betrayal.

Technically, Reinventing Rose is a well-written novel; told in first-person present tense, it has an engaging, at times laugh-out-loud style that Shepherd’s skill makes appear effortless. Who will enjoy it? Fans of chick lit and humorous romance, and anyone who enjoys fun, feel-good fiction.

~

This book contributes towards my Australian Women Writers 2013 Challenge. My thanks to the author for giving me a copy.

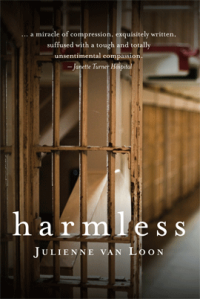

I notice, too, review words like “unsentimental”; it seems to be used often when female literary authors are praised. Sentimentality implies emotional manipulation, and a lack of subtlety and nuance. The term has been used to dismiss the work of a plethora of “female authors”, especially those writing in genres such as romance. But what does “unsentimental” mean? I’m tempted to think it’s code for “writes like a man”, or “give this book a

I notice, too, review words like “unsentimental”; it seems to be used often when female literary authors are praised. Sentimentality implies emotional manipulation, and a lack of subtlety and nuance. The term has been used to dismiss the work of a plethora of “female authors”, especially those writing in genres such as romance. But what does “unsentimental” mean? I’m tempted to think it’s code for “writes like a man”, or “give this book a