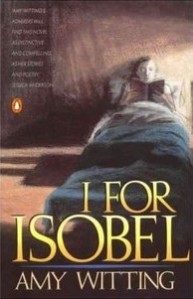

Confession: Amy Witting’s I For Isobel (1989) has been on my shelf for ages and is the first work of hers I’ve read.

Confession: Amy Witting’s I For Isobel (1989) has been on my shelf for ages and is the first work of hers I’ve read.

The novel records a decade in the life of Isobel Callaghan, from unhappy nine to unfulfilled 19. Isobel is a loner, someone who struggles to discern the rules other people live by; she always feels offside, “like being a spy in a foreign country having to pass for a native” (116). As a child, she is treated with barely disguised contempt and hostility by her mother, who favours her sister Margaret; she is bullied at school for being bright; she is haunted by her religious education, her seeming inability to be “good”, as well as her real and imagined misdemeanours.

Orphaned at 16, she goes out in the world to earn her living, finding work as a typist and German translator. She resides first at a boarding house, before taking her own room. Her great love is books – and books by Dead White Males comprise the bulk of her reading: Trollope, Dickens, Byron and, later, Dostoevsky, Auden and Eliot.

Isobel loves words, words to describe the people she meets, the places she goes in mid-twentieth-century Sydney. Words connect her to others, to the students she befriends in a Glebe cafe, to Frank the communist outsider where she works; they are also what separates her. Words are weapons to hurt and be hurt, as well as a balm to cure her loneliness; an oppressor and a liberator. Her mind is a “word factory” which never ceases production.

Eyes open, back to the ceiling: ornate plaster, baskets of flowers linked by swags of ribbon, a stain in one corner, yellow, like… sunshine? butter? honey? paler than pumpkin, darker than pee. Dirty old daylight, if there was a word.

There are words. Words we have plenty of, nasty little buzzing insects that they are. Awake two minutes and the word factory is at it already. And you at the loom, zoom, zoom.

It was going to be a bad day. (128)

Isobel isn’t always likeable as a protagonist: she is too passive; she is a “vacuum” that words rush to fill, a listener, a spectator of life rather than a participant. Her behaviour isn’t always admirable, but it is understandable; she is the embodiment of the phrase, “hurt people hurt people”.

The loosely linked chapters of I For Isobel chronicle Isobel’s travails as she struggles to come to terms with her identity, with her dishonesty (she is a “born liar”), with the half-buried hurts from childhood and misunderstandings that keep her yearning and, for most of the book, unfulfilled. At one moment she glimpses her place as the inheritor of a long line of genes that stretch back into history; as she looks in the mirror, hating her face because it reminds her of her mother, she has an epiphany:

the face shaped and softened with the beginning of a laugh because she was thinking those features weren’t her mother’s; she had had the tenancy of them for fifty years but they had been on the go for generations; that nose had taken snuff, sniffed at pomanders, plague posies, smelling salts, rose hip, orris root – things she had never smelt and never would – as well as honeysuckle, gas leaks and lavender… (137).

The book reaches a gentle crescendo when Isobel returns to the suburb she grew up in and comes face to face with an old foe. The encounter reduces her – and me – to tears. Left sobbing for the sorrow of having grown up in a family that failed her, the only comfort she receives is from the rock against which she rests her cheek, “as rough as a cat’s tongue and unyielding”.

I For Isobel may be the first of Amy Witting’s books I’ve read, but it won’t be the last.

~

This review forms part of my 2016 Australian Women Writers Challenge and Aussie Author Challenge. It’s also part of an effort I wish to make to read more Australian classics.

~

Author: Amy Witting

Title: I For Isobel

Publisher: Penguin

Date and place: Ringwood, Vic. 1989

ISBN: 0 14 012624 4